In

Search of Colombian Cobs

In

Search of Colombian Cobs

A classic introductory article by Frank Sedwick

(First published July 1985 The Numismatist)

(NOTE: Some data might have

been proven different, this study was from 1985)

Cobs are an obscure area of

numismatics unfamiliar to most students of Spanish-American coinage, a fact that

comes as no surprise considering no two specimens of these hand-hammered coins

assume an identical shape, thickness or visible portion of imprint. The cob

coinage of Nuevo Reino, however, is even more mysterious and elusive than that

of the better-known Spanish colonial mints of Mexico, Bolivia and Peru.

Although more has been

learned about colonial cobs in the last 25 years than in the previous two

centuries, researchers have been unable to document enough facts to produce a

definitive reference about Colombian cobs. Without becoming too technical, it is

the purpose of the present study to summarize what is known so far about these

coins and to assess what has yet to be learned.

The Land of

Undiscovered Treasure

Spanish exploration of the

northern-most region of South America commenced about 1500. This territory

encompassed not only present-day Colombia, but also Venezuela, Ecuador and even

Panama, all of which were at one time part of Colombia. The Spaniards designated

the region as El Nuevo Reino de Granada, the “New Kingdom of Granada.”

The Indians called the settlement on the high plain Bacatá, which

conquistador Gonzalo Giménez de Quesada later renamed Santa Fe de Bogotá

in 1538.1

This was El Dorado, the land of undiscovered treasure, named for an Indian chief

who, according to legend, was annointed with gold dust and surrounded by gold

and jewels at Lake Guatavita near Bogotá. Though El Dorado was never found, gold

was indeed abundant in the area, waiting to be mined; silver was mined in small

quantities, but only as a by-product of gold extraction. This fact may explain

why all Colombian silver cobs are rare and why Nuevo Reino was the first

mint in the Americas authorized to produce gold coins.

The Unique Nuevo

Reino Cobs

Whether gold or silver,

Nuevo Reino cobs are characterized by their crudity, inconsistency of design,

and cut. All cobs are crude, but, in general, the workmanship of Colombian cobs

of nearly all periods is inferior to that of Mexico, Peru and Bolivia. The

blundered strike is typical; legends are seldom visible, dates are rare finds,

and devices are poorly etched. Lines that should be straight are crooked,

especially on the gold pieces; tressures (heraldic borders) are unsymmetrical;

elements of the shields are out of proportion; castles look like stylized Indian

gods; and lions take on the appearance of monkeys balanced on their posterior.

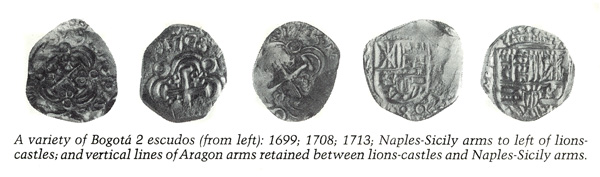

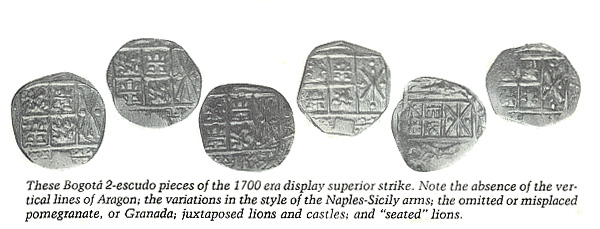

Nuevo Reino, like other

Spanish-American mints, emphasized the shield-type obverse on its early silver

cobs, changing later to the “pillars-and-waves” design, but the variations are

astonishing. (All Nuevo Reino gold cobs, like all silver and gold Mexican cobs,

are of the shield type.) For example, the arms of Naples and Sicily2

should be located to the right of the lions and castles, but just as likely can

be found to the left, a position somewhat akin to displaying the U.S. flag on a

wall with the 50 stars in the upper-right corner instead of the left. Other

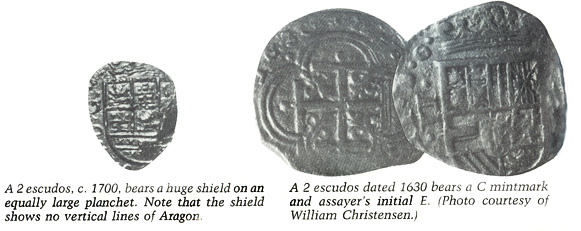

elements of the shield also are sometimes juxtaposed or omitted, such as the

vertical lines of Aragon’s coat-of-arms or the pomegranate (symbolic of

Granada), the latter often located at the bottom of the shield rather than in

the center.

Henry Christensen may have

been the first to point out the gradual disappearance of the Aragon arms, making

Nuevo Reino cobs unique in this respect.3 Also, the quadrants

featuring the two lions and two castles are reversed on Colombian cobs with

great frequency, a phenomenon not exclusive to the Bogotá mint but nevertheless

seldom encountered. In short, the ways in which the shield is depicted on

Colombian cobs reveal that the Nuevo Reino mint employed a number of independent

thinkers.

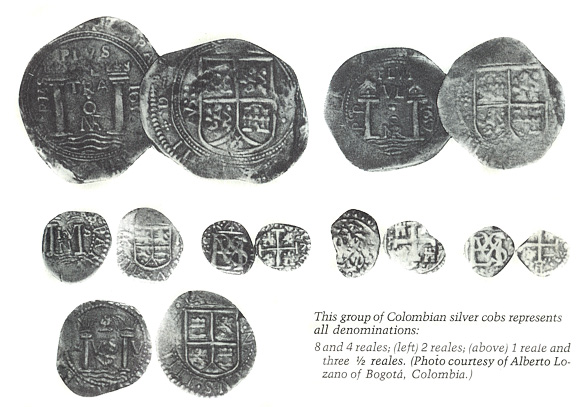

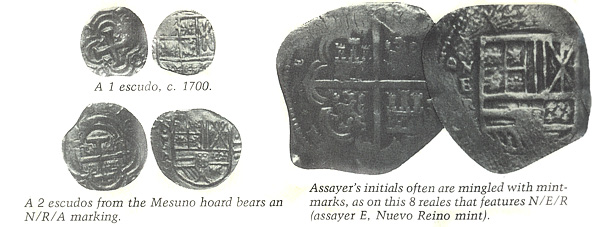

Colombian silver cobs of

the pillars-and-waves design display oddities, too. One cannot be sure where to

look for the date or denomination. The Nuevo Reino mintmark, NR, varies in

monogram as well as location, while the variant SF mintmark (for Santa Fe) can

appear as FS. Assayers’ initials tend to be multiple rather than single;

however, when single initials are used, they are sometimes mingled with the

mintmark, such as NER, or the mintmark itself may be backwards, as in RNE. The

pillars are usually fat and crude, and the legend PLUS ULTRA can be found in any

kind of nine-letter jumble between, above or around the pillars. The lions and

castles on silver cobs of larger denominations occasionally are well executed,

as evidenced by the 8 reales with N/E/R.

Cob authorities and

collectors of experience have identified a typical Bogotá “cut,” which is

representative of most periods but difficult to define. The angles are

uncharacteristic of the products of other mints; even when a Bogotá coin tends

to roundness, its cuts often are abrupt and do not flow into one another.

Especially on later gold of smaller denominations, the cuts tend to incline at

45-degree angles, perhaps because Nuevo Reino planchets usually were thick

rather than broad (the weight remained the same in either case). Their Mexican

and Peruvian counterparts (Bolivia produced no gold cobs) display a more-or-less

perpendicular cut.

Mints and Mintmarks

As early as 1559, efforts

were made to set up a mint in Nuevo Reino de Granada, but for one reason or

another, permission was not granted by the Spanish crown until 1620. At

the time, colonial mints were

considered

to be private enterprises and were granted licenses to manufacture money by the

King of Spain. Mint offices—like those of mintmaster or assayer—could be

purchased, transferred or leased; the bidding for these posts was intentionally

competitive, almost like the sale of a seat on the New York Stock Exchange in

our time. The mintmaster owned the mint for life, or until he sold his

lease or was removed from office for malfeasance. Sometimes the mint’s

owner lived in Spain and never even saw his operation. Not until about

1762 did the Spanish treasury actually begin to take control of the colonial

mints.

considered

to be private enterprises and were granted licenses to manufacture money by the

King of Spain. Mint offices—like those of mintmaster or assayer—could be

purchased, transferred or leased; the bidding for these posts was intentionally

competitive, almost like the sale of a seat on the New York Stock Exchange in

our time. The mintmaster owned the mint for life, or until he sold his

lease or was removed from office for malfeasance. Sometimes the mint’s

owner lived in Spain and never even saw his operation. Not until about

1762 did the Spanish treasury actually begin to take control of the colonial

mints.

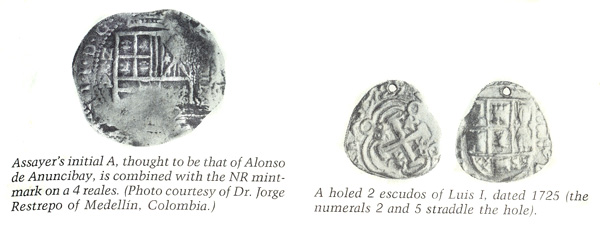

As dictated by Spanish

tradition, the chief assayer’s initial(s) was engraved on a die and struck on

the coin as part of its design, supposedly to guarantee accuracy of weight and

purity of gold or silver content. The initial(s) usually represented the

first letter of the assayer’s given name or either of his surnames.4

Records were kept of the assayers’ names and the dates of their tenure.

Although many are inaccurate or lost, these records are most important today in

identifying the approximate date of an undated cob.

Through the study of such

documents and a royal decree dated April 1620, it is known that Spain’s King

Philip III authorized Captain Alonso Turrillo de Yebra to establish a private

mint in the region of Nuevo Reino de Granada.5 Turrillo was torn

between locating his mint in Santa Fe de Bogotá or in the port of

Cartagena—either way, his precious cargo had to be transported on the Magdalena

River, through mountains and jungles, at the mercy of bandits between the

highland mining center and the coastal point of embarkation for Spain.

Ultimately, he managed to start minting operations in both locations. The

Cartagena facility, the smaller of the two, was characterized by sporadic and

ephemeral production, and probably operated until the mid-1600s. However,

it is a mystery as to which operation was established first and when, and

whether Cartagena produced any cobs other than known non-silver and non-gold

coins.

A partial answer came in

late 1978, when divers located wreckage of the Spanish treasure ship

Concepción, sunk in a storm in 1641 off the northern coast of what is now

the Dominican Republic. Heading for Spanish from Havana with the rest of

the fleet, the Concepción bore the usual Oriental and New World treasures

transshipped from other colonial ports, including Cartagena.

Her cargo was predominately

silver, mainly silver cobs from Mexico and Bolivia; however, one small group of

cobs bore NR or RN mintmarks, mostly with assayer’s initials P or A. In

this cache of Colombian silver cobs were several that featured the rare

assayer’s initial E, a few of which had NR mintmarks while others displayed C

mintmarks.

The C can stand for only

the Cartagena mint. Apparently assayer E, while in Turrillo’s employ,

moved from one mint to another. In the early days of numismatic analysis,

cobs bearing C mintmarks were attributed to the mints of Cuenca or la Coruña in

Spain,6 even though their mintmarks and coinage style were entirely

different from those of Colombian mints.

Other evidence supporting

the Cartagena theory—too lengthy and complex to summarize here—can be found in

Henry Christensen’s Auction Catalog of Treasures from the Concepción

(May 14, 1982),7 in which a handful of Cartagena cobs was offered for

the first time.

The

Mysterious Assayers

Colombian silver cobs

probably were produced at least into the 1720s, with gold cobs struck until the

mid-1750s. The list of assayers presented in Table 2 has been compiled

from various sources, as well as from personal experience. The dates

represent the assayers’ tenures of office as recorded by Barriga Villalba.8

Despite the fact that Barriga had access to all the official documents in

Bogotá, his dates sometimes conflict with assayer-date combinations on the

coins. He lists other assayers (omitted here) whose names do not seem to

correspond with any initials found on coins. Various dates of tenure also

differ in J. Pellicer i Bru’s Glosario de maestros de ceca y ensayadores.9

On the other hand, one whole run of 2 escudos of the early 1700s features

neither mintmarks nor assayers!

The Challenge of

Dating Colombian Cobs

Dates on larger

denomination Nuevo Reino cobs of the pillars-and-waves type are frequently

visible because of their location near the pillars rather than in the

haphazardly-truncated legend near the edge. On both

traditionally-monogrammed ½ reales and the shield types, dates are rarely found,

especially on smaller denominations.11

Despite what various

sources contend, almost any date or denomination is possible, from 1622 well

into the 1720s or beyond. The commonest dates appear to be around the

mid-1600s. No catalog provides a complete listing of dates, probably

because it has not been within any author’s experience to see or document more

than about 70 dates. However, an important hoard of silver cobs was found

in Colombia by Clyde Hubbard, a well-known authority on Latin-American

numismatics, and later analyzed by NeSmith in 1958.12

At this point it should be

reemphasized that Philip III’s aforementioned decree of April 1620, which called

for the establishment of a mint in Nuevo Reino, authorized the minting of gold

coins as well as silver. The Bolivian mint never produced gold cobs, and

the Mexican and Peruvian mints were not permitted to issue them until the late

1600s, after Colombian gold cobs had circulated for many decades.

Philip III died in 1621,

succeeded by Philip IV (designated on coinage as Philip IIII) whose long reign

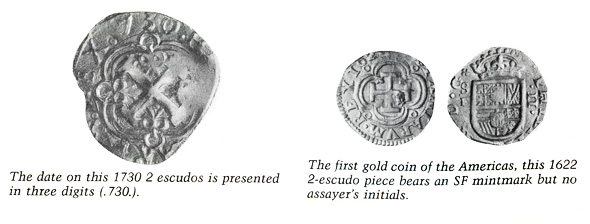

lasted until his death in 1665. A 1622 2 escudos, apparently the first

gold coin of Colombia and the Americas, is illustrated in the 1985 edition of

Monedas españolas desde Juana y Carlos a Isabel II: 1504 a 1868

by Ferrán Calicó, Xavier Calicó and Joaquín Trigo.13 Bearing the SF

mintmark but no assayer, the coin was not listed or illustrated previously in

earlier editions of this prestigious reference (nor in any other book), thus

accounting for the note under the illustration: “Only specimen known and

for the first time pictured. The King’s numeral [III] quite clear.”

By its design and technical

workmanship, this great rarity is obviously of higher quality than all

subsequent Colombian gold cobs. Perhaps the dies were made in Spain (where

it was not known who was to be the assayer in Bogotá) and transported to the New

World during the lifetime of Philip III, whose numeral the coin bears.

This would explain why the coin—the only Nuevo Reino cob issued prior to

Philip IV—is listed in Calicó’s book under Philip III.

Although the months of

delay between the cutting of the dies in Spain and their slow transportation

across the Atlantic and inland to Bogotá is understandable, how can a 1622 date

be reconciled with a coin bearing the numeral of Philip III, who died in 1621?

Perhaps news of the king’s death had not reach Bogotá by the time the pieces

were minted. However, if they had the expertise to reengrave a date, why

couldn’t they also add an assayer? Maybe the date was not reengraved but

merely representative of Spain’s foresight as to when the dies would arrive in

the New World (a theory that seems farfetched). Calicó offers no

explanation.

Just last year, another

specimen of this rare 2 escudos came to light. A comparison between the

Calicó specimen and the second piece suggests both were struck from the same

dies; however, the latter is inconclusive as to the king’s numeral and lacks all

but a tiny, raised portion of the final digit of the date. The final 2 in

the date on the Calicó specimen also is raised higher than the first 2.

This observation, coupled with the fact that the pieces were likely struck from

the same dies, is evidence that the coins share the same date.

The Calicó piece gives no

evidence of a reengraved final digit, neither on visual inspection nor by

mention of the authors. Once again, if the present coin had been struck in

Bogotá with a reengraved final numeral after the year 1622, is it not likely

that the people at the mint also would have added an assayer’s initial?

Whatever the answer, these two coins must represent the earliest gold coins of

the Americas. Whether struck in Spain or Colombia, the coins possibly were

presentation pieces—two of a very limited few—and not intended for circulation.

Also known is a 1630 2

escudos (C mintmark, assayer E) that is too crude to have been produced in

Spain, yet Calicó shows a 1630 with clear C/E listed under Cuenca, Spain, and

has no listing for Cartagena gold. Despite Christensen’s analysis and

auction of Cartagena cobs in 1982, various prominent numismatists still seem

unconvinced that a mint was ever established in Cartagena.

In the possession of Henry

Taylor, a treasure salvor who lives in the Florida Keys, is a document from the

General Archives of the Indies in Seville, Spain, written in Old Spanish.

Dated August 31, 1630, the document outlines in detail the plans for a mint

building to be located in Cartagena on Calle de la Cruz, suggesting that the

Bogotá mint was established (in 1622, of course) before the Cartagena mint,

rather than vice versa, as most who accept the existence of the Cartagena mint

believe. But, who knows whether the document refers to the original

establishment of the Cartagena mint or to a new Cartagena facility replacing an

old one?

Less puzzling is an almost

entire run of Nuevo Reino 2 escudos dated between 1627 and 1663. Many 2

escudos of this style and its variants were represented in the so-called Mesuno

hoard,14 found in 1936 near the Colombian town of Honda on the banks

of the Magdalena River. Most of the hoard was comprised of 2-escudo pieces

bearing the NR mintmark and assayer’s initial A. No other Colombian gold

denominations

appear to have been minted during the reign of Philip IV (1621-65).

The original decree of Philip III authorized coins in denominations of 1 and 2

escudos, although I have not seen any 1-escudo pieces from this period.

Moving on to the reign of

Charles II (1665-1700), I am aware of no 8- or 4- escudo pieces, only a few

undated 1-escudo coins and a handful of 2 escudos dated between 1671 and 1699.

Though unrecorded in any book, the 1695 and 1699 issues do exist, as evidenced

by the 1699 2 escudos pictured here.

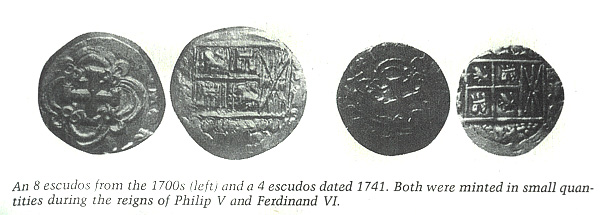

It seems that 4 and 8

escudos were first minted in small numbers in the 1740s during the second reign

of Philip V (1724-46) and during the reign of Ferdinand VI (1746-59) until 1756,

probably the final year of Nuevo Reino cob coinage. However, the 2 escudos

produced during the first reign of Philip V (1700-24) are another story.

These 2 escudos are now the

commonest Colombian gold cobs, although before the salvage of a 1715 Spanish

fleet sunk off the east coast of Florida (which began in the early 1960s and

continues even now) they were extremely rare.15

It might be wise to pause

for a moment to discuss the chronology of royal succession, which can be

particularly confusing for those who are unacquainted with Spanish history.

Charles II was king of Spain from 1665 to 1700, and Philip V reigned from 1700

to 1724, the year in which he abdicated in favor of his 16-year-old son, Luis.

Luis I died later that same year, whereupon Philip reoccupied the throne from

1724 until his death in 1746, hence the period known as his second reign.

In a perplexing series of

events, Philip V, a Bourbon, was sponsored by the French and opposed by the

English, Dutch and Austrians, who in 1701 formed an alliance to replace Philip V

with the Archduke of Austria, who is known to history as the Pretender Charles

III (not the same as King Charles III of Spain, who reigned from 1759 to 1788).

Subsequently, a civil war, referred to as the War of the Spanish Succession,

broke out in Spain in 1702 and spread throughout Europe. In 1713 the

Treaty of Utrecht brought an end to the war and confirmed Philip V as king of

Spain and her dominions in the Americas, much to the chagrin of the autonomous

republic of Catalonia and its capital Barcelona, which had been aligned with the

Pretender.

Thus, listed in Calicó’s

Monedas

under Charles III, Archduke of Austria, is a group of Colombian 2 escudos dated

consecutively between 1701 and 1713 (with the exception of 1702), as well as

Colombian 8 reales of 1702 and 1705. No coins of the other New World mints

are included. The only logical assumption is that somehow the authorities

in Bogotá favored the Pretender and that the use of the legend CAROLVS (Latin

for Carlos or Charles) on Colombian 2 escudos was quite intentional, rather than

a result of a communication lag after the death of Charles II in 1700s. On

the other hand, I have yet to find CAROLVS followed by a III instead of a II on

these coins.

Calicó lists A as the

assayer for this group of 2 escudos dated 1701-13. I have seen hundreds of

these coins and have yet to find one with any visible assayer or mintmark, the

absence of which cannot be accidental. Not illustrated here, yet in my

possession, are several typical specimens on which the legend CAROLVS II D.G.

runs closely around the entire periphery of the shield, leaving no space

whatsoever for mintmark-assayer designations. Was this the Colombians’ way

of promoting the Pretender, using the legend CAROLVS well into the 1700s but at

the same time avoiding legal responsibility for doing so?

A Wealth of

Information

The sunken fleet of 1715

was laden with far more coins and treasure than usual due in large part to the

War of the Spanish Succession. During the conflict, the treasure fleet’s

semi-annual voyages from the New World had been curtailed or reduced to an

occasional few ships, causing coins to pile up in the colonial mints, from which

they could not be transported in quantity until after the Treaty of Utrecht.

According to the late W.

Frank Allen in his article “History Revealed: Previously Unknown Spanish Gold

Coins,”16 not only was Calicó aware of the work of the salvors of the

1715 fleet, but he also traveled to Florida in late 1964 to inspect the finds.

Thousands of Bogotá 2 escudos were salvaged, but only fourteen bore dates: 1672,

1687, 1697, 1701 (two specimens), 1703, 1704, 1705 (two specimens), 1707, 1708,

1709, 1712 and 1713.

Rarely does the date not

run off the planchet of Bogotá 2 escudos of this period, which spans not only

1700-15 but also the entire previous reign of Charles II, as evidenced by cobs

dating to the 1600s that were salvaged from the wrecks of the 1715 fleet.

Prior to this salvage, what had been particularly mysterious, however, was the

absence of Spanish-American gold cobs of the early-1700 period.

Calicó himself wrote the

preface for an auction catalog entitled

Spanish Galleon Treasure,

which offered the bulk of the salvaged material in a public sale conducted at

New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, November 27-29, 1972, by Schulman Coin and

Mint. To Frank Allen’s list this catalog added the 2-escudo dates of 1706

and 1710. A later Schulman auction held December 2-4, 1974, offered the

treasure from the

Maravilla, sunk

off the Bahamas in January 1656 (too early for most colonial gold coins, with

nothing significant in Colombian gold cobs), as well as a second and less

important offering of 1715-fleet coins, in which all the Colombian 2 escudos

were undated.

The material from the 1715

fleet later was offered publicly—and for the last time in quantity—in Bowers and

Ruddy’s Auction

Catalog of the 1715 Treasure Fleet,

February 17-19, 1977. In addition to the hundreds of descriptions and

photographs of original pieces, the catalog carries an entire section about

coinage of the Bogotá mint (though not all data are correct) and excellent

artistic renderings of various changes in design of the shield pictured on

Bogotá gold cobs. However, the catalog adds no new dates to the Hans

Schulman and Frank Allen lists of dated 2-escudo cobs.

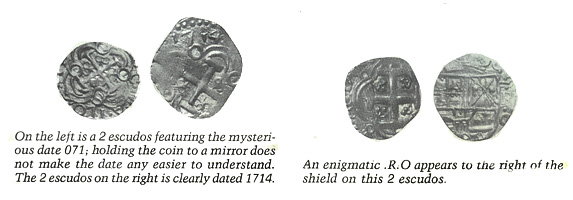

To all the lists we can now

add a 1714 2 escudos. My own feeling is that all dates exist, 1700-14, but

I have no knowledge of a 1715-dated piece from the wreckage. Among the

salvaged Mexican gold cobs of all denominations, a number of 1715 pieces have

been found (very recently in quantity), although overall that date remains more

elusive than 1713 and 1714; among Lima pieces, it appears that 1713 was the

latest date on any denomination represented in the fleet’s cargo.

Remember, the fleet sank in

July 1715 with not more than a half-year of possible production of 1715-dated

coins. Why the Mexican coins of that year and at least some 1714-dated

Colombian cobs were available to be shipped with the fleet, while Lima pieces

were not, is unknown.

Through the years, I have

been privileged to examine hundreds of Colombian 2 escudos salvaged from the

remnants of these ships. Most of them have entered the market as the

property of the divers themselves or the investors in various salvage

enterprises. The State of Florida has a 25-percent share in any treasure

found off its shores and thus owns a quantity of these pieces, some of which are

displayed at the Museum of Florida History in Tallahassee.

A great majority of these 2

escudos shows some portion of CAROLVS II to the right of the shield, and

consequently it was logically assumed that most of those that sank to the bottom

of the ocean in 1715 actually were minted before the death of Charles II in

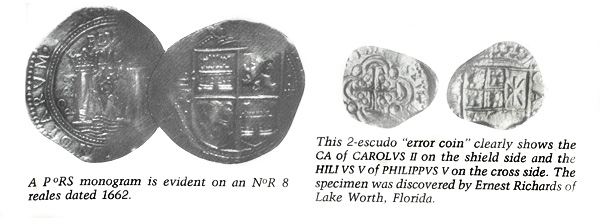

1700. However, we now have a different interpretation. In my

possession is a 2 escudos that features portions of CAROLVS by the shield on one

side and parts of PHILIPPVS or PHILIPVS V (the V is quite prominent) on the

other side where HISPANIARVM should be.

Although this is obviously

an “error coin,” the important feature is that the shield is the same as that on

most CAROLVS pieces, thus providing additional evidence that the typical Charles

II shield, even with his name beside it, was retained well into the 1700s, not

just a year or two after the death of Charles II but up to as late as 1714.

In short, the legend CAROLVS is not a reliable indication of when the coin was

minted.

Regarding coinage issued

after 1715, a Nuevo Reino 2 escudos of Luis I, dated 1725, does exist,17along

with numerous other Colombian cobs bearing dates of the second reign of Philip V

through 1756, the year that marked the end of Nuevo Reino cob coinage.

Unanswered Questions

(at the time of the

publication)

In the broad field of Colombian gold and silver cobs, a number of mysteries must

be solved:

-

We need to know the

entire story of the Cartagena mint. What were its years of production

and what was its specific relationship to the Bogotá mint? How many

other Cartagena gold cobs have surfaced in addition to the specimen pictured

here? Aside from the C mintmark, were early NR mintmarks also used in

Cartagena? Where exactly on the Calle de la Cruz was the mint, and why

are there no further records of its operations or construction, especially

considering that most colonial houses and buildings, or at least their sites

within the old walled city, are still intact, as are the walls themselves?

-

Where are all the

Bogotá silver cobs? Granted, production was not large compared to that

of Mexico, Bolivia and Peru, yet the most extensive collection I have seen

(which was in Bogotá) numbers only about 25 pieces. Who collects

Bogotá silver cobs? Please come forth and let us study your coins!

-

Why don’t official

records of assayers’ names and tenures, as listed by both Barriga Villalba

and Pellicer I Bru, correspond to each other or to actual dates on many

coins? Does the assayer’s initial T represent Turrillo himself, even

though he was the mint’s lessee and not its assayer? Who were assayers

E (both early and late) and VM? Was the late assayer A the same as

assayer ARC? If not, who was he? Why are asssayers’ initials so

often multiple, contrary to the practice of other colonial mints? Why

is the assayer’s initial omitted on what must be presumed to be the first

gold coin of the Americas, and where was this coin designed and minted?

-

Why did the Colombian

mints either omit or systematically relocate the pomegranate (or “Granada”)

on the Nuevo Reino de Granada coat-of-arms, when by the very name of the

province one would expect it to be prominent? Why did the Aragon

coat-of-arms gradually disappear from the king’s shield on most Colombian

gold cobs? Why were the positions of the lions and castles so often

juxtaposed?

-

Why were gold and

silver Colombian cobs so crudely designed and struck, when the labor

(untutored Indians) and equipment were hardly less primitive in the colonial

mints of Mexico, Bolivia and Peru?

-

What is the reason for

the frequent inversion of the SF mintmark, when FS (“Fe Santa”) makes no

sense? Likewise, one wonders about NR and RN, although “Reino Nuevo”

is linguistically easier to defend.

-

Why were so many 2

escudos but so few 8 escudos minted in Colombia, while in Lima the opposite

seemed to be true? (Mexico seems to have produced nearly equal

quantities of 2- and 8-escudo coins; 4-escudo pieces from all mints are

scarce.)

-

Did Colombia indeed

support the Pretender Charles III from 1702 to 1713? If so, does

Colombian coinage reflect this attitude?

Sunken Spanish galleons

await salvage off the shores of Cartagena today. The sites are known, but

requests for permission to explore the wrecks have yet to be worked out with the

Colombian government. With today’s advanced techniques of salvage,

reclaiming sunken cargo is no longer a vague, romantic adventure but a

scientifically- and economically-sound enterprise, if properly funded and

researched. Imagine what these ships could yield!

Hundreds of thousands of

unexamined, uncataloged bundles of inventories, ships’ manifests, reports,

charters, legal agreements and royal correspondence are held by the General

Archives of the Indies in Seville and the House of Trade in Simancas, Spain.

Treasure divers have sifted through some of this voluminous material, but has a

numismatic team of cob specialists done so? The answer is no. By and

large, treasure salvors are neither researchers nor numismatists, and frequently

discover the rarity of their finds only after the fact.

Given great patience, much

could be learned from the material in Seville and Simancas about cob production

and distribution in the New World, but who will fund such a venture? The

questions of funding aside, who will take the time to carry out such research?

Apparently, not even Spanish numismatists have done so.

Colombian Cobs and

the Numismatic Market

Colombian gold cobs are

vastly undervalued in the marketplace, as there are virtually no collectors to

compete for them. Much of the reason for this is the unavailability of

literature; most of what little does exist is written in Spanish.

Over the years, I have

spent much time in Colombia as a traveler and resident, but I have never met nor

heard of a serious collector of Nuevo Reino gold cobs. Not long ago, two

rare gold cobs of Bogotá came into my possession—a 4 escudos and an 8

escudos—and I almost gave them away for lack of a buyer. Undated 2 escudos

salvaged from the 1715 fleet are not hard to find and are sold mostly as

pendants, but collectors of dated 2-escudo cobs are as rare as the coins

themselves. A year ago the extremely rare Cartagena 2-escudo piece sold

for a relative song. As knowledge increases, this situation must change.

No informed collector

doubts the rarity of Colombian silver cobs. These pieces sell for much

more than Colombian gold cobs and comparable silver cobs of other colonial

Spanish-American mints, yet the market remains very small and suffers form a

scarcity of information, as in the case of Colombia’s gold issues.

When a famous American

financier was asked the secret to his success, his laconic reply was, “Buy a

straw hat in January.” Perhaps January is on the horizon, and Nuevo Reino

cobs will prove to be straw hats of the numismatic marketplace.

Biography:

Numismatic pioneer Frank Sedwick, Ph.D, was born in 1924 in Baltimore,

MD, and earned degrees from Duke University, Stanford University and the

University of Southern California. After a wartime stint in the Navy, Frank

became a career professor of Spanish and Romance languages, which he taught at

the Naval Academy, Ohio Wesleyan, Wisconsin-Milwaukee and finally Rollins

College in Winter Park, FL. At Rollins, while earning royalties as the author of

several standard textbooks in the field, he took the position of Director of

Overseas Programs and made frequent visits to Spain and Colombia, where his

interest in Latin American numismatics began, although coins had been his hobby

since childhood.

In 1981 Frank

left academia forever and became a full-time coin dealer. At first his focus was

modern Latin American coins, but soon he realized that there was a niche in

cobs, which had not been properly researched for the average collector to

understand and appreciate. Thus was born The Practical Book of Cobs (now

in its 4th edition, 2007), which was perfectly timed to satisfy new cob

collectors generated by the fabulous Atocha find by Mel Fisher in 1985. For well

over a decade Frank was considered the authority on cobs, his main area being

gold cobs from the 1715 Fleet, thousands of which went through his hands.

In 1991

Frank authored his second numismatic book, The Gold Coinage of Gran Colombia,

in order to update the existing references in his own area of collecting

interest. Frank's collection of Colombian Republic gold coins is still one of

the finest ever put together

Frank's son

Daniel joined him in business after college in 1989, full time in 1991, after

many summers of "interning" with him at the various ANA shows. In 1996, with

plans to retire that same year, Frank died unexpectedly, leaving the business to

his son. Daniel has continued the coin business and book authorship ever since.